At Sea Ranch buildings were designed to be integrated into the landscape.

Utopian or pragmatic, celebrated or untested—cities, communities and structures that work for the benefit of nature and humankind are featured in our new update.

How can buildings– and cities– do more than create habitable space? How do we align architecture and urban design with nature? How do we transcend the traditional notion of the urban grid? What are the benefits of looking to nature as the solution? We showcase several legacy projects from the 1960’s to ‘80s, inspired visions of designers, architects and urban planners who believed that nature plays a big role in where and how we should build.

Courtesy of the Biomimicry Institute

Then we turn to what’s happening today. Small examples and bold contemporary projects are underway– London as a national park city and Copenhagen’s plans for nine new energy islands; Jeanne Gang’s vision of green islands in the sky (Chicago); the brilliant ideas of Janine Benyus to adapt the ecological services of species and ecosystems for cities and buildings. We wrap up with a prototype for the future — a tiny, environmentally friendly house that can be used to grow food, generate clean water, and clean the air

These are bold ideas for making cities and places that offer deep environmental benefits and services.

Are politicos, planners and designers listening? We hope so.

(Our thanks to Inhabitat, Dezeen, Dwell, Fast Company, Bloomberg and GreenBiz for their superb reporting.)

remarkable legacy projects

Pacific Coast, Sea Ranch

Sea Ranch, the original masterplan by Lawrence Halprin

Sea Ranch logo

Along 10 miles of Pacific Coast about two hours north of San Francisco, Sea Ranch was the locus of inspired development starting in the 1960’s – a marriage of nature and community with the goal of preserving the area’s coastline, its rugged beauty, and forests – in other words, minimizing the impact of planned development on the natural environment. A new exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art , details the early concepts and plans of this seminal Northern California Modern development that encompasses 3,500 acres ( on view through April 28)

Lawrence Halprin

In 1963, landscape architect Lawrence Halprin designed a community masterplan sensitive to the 3,500-acre site on both sides of US Highway 1, its existing landscape features, plantings, and microclimates. Design requirements and materials were intended to minimize the impact of development and alter the natural landscape as little as possible.The plan was based on California’s indoor-outdoor lifestyle, as a place for weekenders to enjoy community while they escaped from the urban scene. Halprin had experienced the shared purpose of communal living on a kibbutz for several years in Israel before he entered Cornell University. A select group of architects then set to work on designing condos, single-family homes, a lodge-style inn, recreational facilities and a small town center.

Architects Richard Whitaker, Donlyn Lyndon, Charles Moore and William Turnbull were designers of some of the earliest buildings at Sea Ranch. Here they are at Sea Ranch condo #1 in 1991.

“[Halprin’s] master plan prioritized large swaths of shared meadow and specified that 50% of Sea Ranch land be set aside as common “open space.” [Remember, this was the 60’s!] Ideas included capturing water from the Gualala River in wells to support the community, mitigating the gale-level oceanic wind through thoughtful tree planting and thinning the looming forest to bring in sunlight. “

First condo at Sea Ranch, on the ocean-front side. Photo by Kate Reggev

Sea Ranch brochure designed by Barbara Stauffacher Solomon (1965)

In my two 1970s visits, Sea Ranch was a marvel of repose – a place to experience the wild and windy Pacific Coast with paths to craggy oceanfront where it was possible to climb out during low tide and watch marine life in tidepools. A small ocean-side lodge called Sea Ranch allowed paying guests the chance to spend a few days in a natural setting, with spectacular views of the Pacific Ocean .

Rush House at Sea Ranch. Photo by Kate Reggev

Across US Highway 1, the wooded areas of Sea Ranch were scattered along the Gualala River, banked by a deeply forested area, another haven of tranquility. Overall, some 1800 homes were completed, but inland California residents – fearing overdevelopment—succeeded in the early 70’s in getting a 10-year moratorium on further building, especially on the ocean-front side.

Sea Ranch, Rush home interior. Photo by Leslie Williamson.

Sea Ranch still has room for growth (another 600 homes) so we’ll watch to see what the next generation produces. A new book awaits you: The exhibition catalogue The Sea Ranch: Architecture, Environment, and Idealism published by Delmonico Books/Prestel is available for $37.50

Dwell Magazine’s beautiful pictorial essay on Sea Ranch

Arcosanti in the Desert

Landscape shot of Arcosanti

Paolo Soleri’s utopian model urban community in the high Arizona desert – Arcosanti –was conceived in 1970 as a solution to urban sprawl that was gobbling up farmland to create suburbs and the resulting costs of growth — loss of farmland and habitat, expanded energy use, inadequate transit, lost time and productivity from commuting.

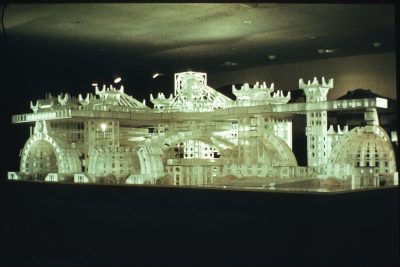

Model of Arcosanti

Soleri’s philosophy of creating compact city design, was summed up as Arcology — “ architecture and ecology as one integral process…capable of demonstrating positive response to the many problems of urban civilization…. A city should similarly evolve, functioning as a living system. “

Arcosanti Apse Courtesy of CodyR Wiki commons

“Arcology recognizes the necessity of the radical reorganization of the sprawling urban landscape into dense, integrated, three-dimensional cities in order to support the diversified activities that sustain human culture and environmental balance.”

Dome House at Arconsanti was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright

Arcosanti is an ongoing work-in-progress– created literally from the sweat and enthusiasm of thousands of “workshop participants”—volunteers who pay to come onsite and help continue building the community. Arcosanti continues to inspire and motivate: Every year some 8,000 people participate in workshops to keep building Arcosanti; and 40,000 people come to visit this unique habitat.

Greenhouse at Arcosanti

A related story by Motherboard: The City of the Future is Hiding in the Desert

Nature flourishes in Hundertwasser’s Enclave

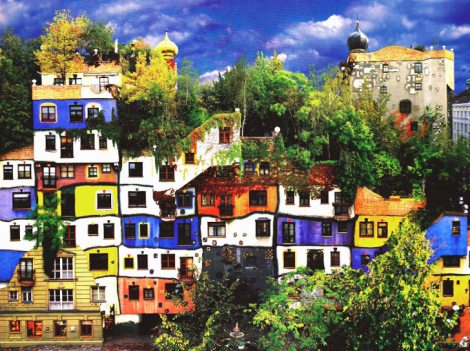

Hundertwasserhaus in Vienna, Austria

In Vienna, an apartment block in the Kegelgasse District is awash in color, undulating floor heights, variegated windows –and lush vegetation. It was conceived by artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000) with architect Univ.-Prof. Joseph Krawina as a co-author and architect Peter Pelikan as a planner. Hundertwasser rejected the straight-lined modular grid and aligned his ideas with his love of nature, with a colorful, dream-like façade, an endorsement of the irregularity and quirkiness we find in nature. If you don’t look closely, you’d think it is an oversized mural painted by the artist and set into the neighborhood.

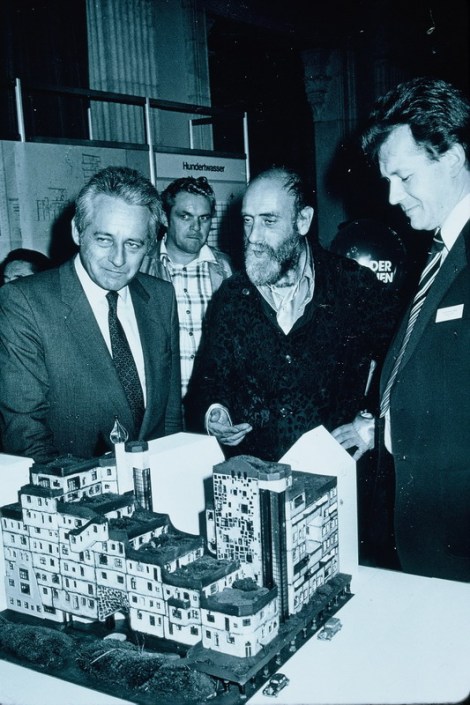

Hundertwasser and Mayor Gratz (left)with model

In fact, Hundertwasserhaus contains 53 one- and two-story apartments, four offices, 16 private terraces and three communal terraces. 900 tons of soil was excavated from the site was returned to make a grassy roof and fill up planters. Hundertwasser was on the construction site every day for a year. On the opening day, February 17, 1986, some 70,000 people visited Hundertwasserhaus.

Model of the Terrace House, another Hundertwasser design

Built between 1983 and 1985, Hundertwasserhaus could be described as a one-off, but it succeeds as a powerful vision of one man’s vow to align nature with architecture. Hundertwasser decried the urban grid and committed to match every foot of built space with an equal amount of vegetation: he succeeded. Today’s façade is bathed in vegetation—perhaps a forerunner to the contemporary green walls movement in Paris and elsewhere promoted by (Patrick Blanc)

Hundertwasser philosophy: “This house is intended as first approach to a conversation with nature, in which we and nature are equal partners; one may not overpower the other.”

the contemporary scene

London as the First National Park City

Regents Canal London

It’s a city – NO, it’s a park! Daniel Raven-Ellison looks at London and sees both. Mere mortals look at Greater London as a booming, built-up metropolis of nearly 9 million, with cars, congestion and air pollution, but Raven- Ellison sees millions of trees, vast expanses of urban nature (parks, landscapes, the Thames and its tributaries) and the potential to improve habitats, the quality of life and the resilience of this city. He calls the idea a National Park City. It would be the first of its kind.

This is the city, by the way, that created a congestion tax to discourage suburban commuters from driving into town and further polluting its already polluted precincts.

Tower of London

London Mayor Sadiq Kahn buys the idea, and so too did those who supported the crowdfunding page that has generated over $41,000. The Mayor announced plans in August 2018 to make London the world’s first National Park City, and sometime this year it will probably become official.

Alexandria Park London. Courtesy of Wikipedia

Daniel Raven-Ellison

London shares its urban streets, soccer fields, parks and ponds with some 15,000 species. Raven-Ellison, who is a geographer and former teacher, thinks London can boost its National Park assets by making more than half its total area green – more green roofs, green walls, and rain gardens—ideal habitats for wildlife. Right now about 47 % of the city is “physically green” (a surprise!) with golf courses, gardens and natural areas

If you’re in Washington DC on March 21, Raven-Ellison will be part of a National Geographic Explorers panels that looks at Cities of the Future, in conjunction with the Environmental Film Festival.

Island in the Sky – Building an Ecological Roof

Studio Gang ecological roof, Chicago.

A 5,000-square-foot green roof – a functioning prairie ecosystem with grasses, wildflowers, shrubs and trees— sits atop the 1938 Art Deco building in Chicago that houses Studio Gang, headed by in-demand architect Jeanne Gang. Chicago is among 10 top U.S. cities that have green roofs designed to offset the urban heat island effect, absorb rainwater and improve drainage to help reduce flooding. Washington DC is ranked #1 with over 1 million square feet (it’s probably the Pentagon roof!) See Smart Cities Dive

Ecological roof also has an adjacent treehouse pavilion for workshops and activities. Photo by Tom Harris.

Gang contends green roofs can be more. “This unique green roof– is a living laboratory,” says Gang, “where we’re working with ecologists and other specialists to build a body of knowledge—and eventually, best practices—about how urban rooftops can become an ecological network of green spaces that cultivate much-needed biodiversity.” Vimeo interview with Jeanne Gang.

Bioblitz on the Studio Gang rooftop

The firm has conducted a bioblitz for each of the two years since the roof was installed, with scientists and others scouring the roof to look for critters.

Turns out, it’s a haven for bats, birds and bees, and much more. The second bioblitz uncovered 71 species living atop the roof, including three colonies of bees managed by Chicago Honey Co-op.

The rooftop also has other uses: It is complemented by a transparent glass “treehouse” pavilion – an adjacent indoor space – that can be used for workshops, office events, yoga, and community public events.

The Gang studio wants to see a bigger movement in which ecological green roofs form a network across Chicagoland – islands in the sky – that will support region-wide biodiversity. It’s a great idea, not just for Chicago, but also in cities where development is rampant (Seattle, Vancouver. Los Angeles, New York); pollution is decimating bird and insect populations; and it’s difficult to create new park land or street-level green spaces.

Island in the Sky digital bookcover

The rooftop prairie’s black maple, bur oak, and downy hawthorn trees require increased soil depth to allow for root growth. To accommodate the extra weight of the tree mounds, they were planted in line with the interior columns of the building.

The studio has produced an illustrated pocket-size booklet that describes the plantings, the species they’ve found, and insights from scientific collaborators working with Studio Gang. Use the guide to get perspectives on rooftop ecology and its future potential in your city, whatever its size. Island in the Sky, the field guide to their rooftop ecosystem.

Islands in the Øresund – Copenhagen

Sketch of Holmene from the airport

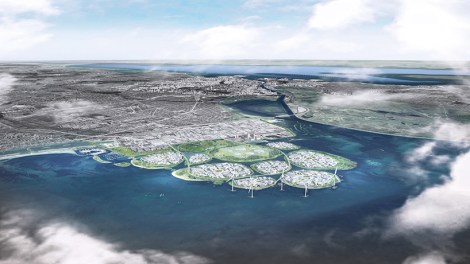

In a bid to shed dependence on fossil fuels, the Danish government is moving ahead with plans to create nine artificial islands with an industrial energy focus—called the largest land reclamation effort in Scandinavia – at Hvidovre, just 10 kilometers south of Copenhagen on the coast of the Øresund. Scheduled to begin construction in 2022, Holmene (the Islets), will be multi-faceted – and environmentally friendly — as a fossil fuel-free generator, tech center, recreation and sports center for the public, protective flood barrier for the coastline, and an area of “untouched nature” including reefs and areas of no-public entry, to improve biodiversity in the region. Plans for the project were drawn up by Copenhagen-based architecture and planning firm URBAN POWER .

Drawing of the energy/tech islands with cycling trails and other public features

The Holmene project has several new twists: it will boast the largest waste-to-energy plant in Northern Europe: the bio and waste water of 1.5 million people will be converted into clean water and biogas. It will run entirely on clean energy production—including 5 six-megwatt wind turbines. It will furnish enough power to cover 10% of Copenhagen’s total electricity consumption – and it is a carbon emissions reducer: 70,000 tons each year.

Some 26 million cubic meters of soil reclaimed from the region’s subway and building projects will be reclaimed to construct the islets, a total of 3-million-square meters of land and natural flood barriers (about 741 acres).

Another schematic showing the islands offshore from Hvidovre, a suburb of Copenhagen about 10 km south.

Approximately 2.3 million square meters will be dedicated to industrial areas, the remaining land developed as natural landscapes for sports and recreation, including 11 miles of cycle routes. Holmene’s first island will be completed and habitable by 2028, and total project completion by 2040.

Projected aerial view of Holmene completed in 2040

The Danes’ Dutch neighbors have been reclaiming land from the sea, lakes and marshes for hundreds of years—about 17% of their land, 7,000 square kilometers, is reclaimed– including expansion of the Port of Rotterdam and the province of Flevoland, which is almost entirely reclaimed from the Zuiderzee.

What Can We Learn from Nature ? Biomimicry & the Genius of the Biome

What is biomimicry?

Finding innovation inspired by nature is the mantra of Biomimicry3.8, a nonprofit consultancy that works with cities, planners and architects, colleges, companies and entrepreneurs looking for sustainable solutions. Imagine using the genius of animals, plants, habitats and natural systems to build more resilient buildings and cities!

Janine Beynus, cofounder

Janine Benyus – co founder of the Biomimcry Institute and Biomimicry 3.8 – is a biologist, multi-book author, and all-round inspired advocate for using nature’s examples and lessons to solve problems.

Her philosophy: “The core idea is that nature has already solved many of the problems we are grappling with. Animals, plants, and microbes are the consummate engineers. After billions of years of research and development, failures are fossils, and what surrounds us is the secret to survival.”

Don’t miss this interview with Janine Benyus

Biomimicry is learning from and then emulating nature’s forms, processes, and ecosystems to create more sustainable designs. That idea is a word she invented to describe the concept.

Cover of Biomimicry

Benyus produced a seminal work — Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature (1997) – popularizing the term and inspiring new approaches to problem solving. (A great example is the sticky foot pads of the gecko that inspired the development of a new adhesive.) Read the first chapter of her book

What she calls “the genius” of the biome” is not an environmental pipedream – it’s a concept that is catching on in the design of factories, buildings, campuses, and cities.

“When the forest and the city are functionally indistinguishable, then we know we’ve reached sustainability.” – Janine Benyus, Biomimicry 3.8 Co-founder

Beynus says, “The answers are all around us.”

In a recent Greenbiz one-hour presentation, Benyus and Paul Woolford, a senior vice president at the architectural firm of HOK, discuss how the” idea of buildings as a regenerative force” can make significant contributions to how we design cities and buildings, and make positive contributions around the world.

Learn more about the Biomimicry Institute

Biomimicry Workshops and Foundational Courses (prices start at $65!)

A Tiny House Emulates Nature: Clean Air, Clean Water and Food

ELM self sufficient home photo by Esto, All rights reserved

Imagine a tiny house—just 22 square meters, or about 200 square feet — that can meet the climatic conditions of New York, with its cold winters and hot summers. Its environmental features include a dedicated outdoor plant-growing wall for microfarming to provide food; plant-based air purification; solar-powered energy; and filtering to provide clean water.

Steps up to the sleeping loft

Ecological Living Module (ELM) for the United Nations Environment Programme is a prototype “tiny house” that is self-sufficient – there’s a loft bed, storage, compact kitchen that make the best use of this limited space. It’s made of renewable bio-based building materials.

Ecological living module panels at the UN exhibition in 2018.

Why now? Why not? The UN Habitat Program reminds us: “The housing sector uses 40 per cent of the planet’s total resources and represents more than a third of global greenhouse gas emissions.”

The project is a design created by UN Environment and the Center for Ecosystems in Architecture at Yale University, in collaboration with UN-Habitat, and with Gray Organschi Architecture.

ELM was constructed and on display at the United Nations Headquarters Plaza in New York, in July and August 2018. It took 4 weeks to fabricate and 2 days to install! It’s intended “to spark public discussion and new ideas on how sustainable design can provide decent, affordable housing while limiting the overuse of natural resources and climate change.”

Is this a revolution ? You bet! New designs are being drawn up to suit the climate and cultural context in Quito, Ecuador, and Nairobi, Kenya. Imagine affordable, environmentally self-efficient housing for a billion people. Let’s start thinking of how this can be brought to scale. View the pictorial essay

.